The Strange Things We Come Across in Second-Hand Books

Tasneem Pocketwala finds herself drawn to a mysterious trail of belongings left behind by strangers in second-hand books. She speaks to fellow book lovers about these found objects and how they unintentionally tie them to people they’ll never meet.

In the poem “Marginalia”, the poet Billy Collins pays an ode to the act of scribbling along the margins of books as we’re reading them. He talks about the various things people do on the “white perimeter” that they claim for themselves: they fight with the writer, or cheer them on, or modestly make simple analytical notations of the text at hand. Collins goes on in this way for a while, and then he tells us about the one “marginalia” that has stuck with him for a long time, ‘dangling from me like a locket’, he says. It was written in a borrowed copy of The Catcher in the Rye alongside greasy smears, and it said, “Pardon the egg salad stains, but I’m in love.”

There is something poignant about coming across a remnant of a stranger’s life, with whom the only link you have is that both of you found one particular book interesting enough to pick up to read. This is one of the charms of second-hand books – the fact that it has had a previous life entirely unbeknownst to a new owner. It has passed through the hands of people the new owner is unlikely to meet. There is a kind of sentimentality in that line of thought, but there is also romance.

Marginalia in old books is all about leaving an imprint of the thoughts and feelings you have as you – like Maria Popova says somewhere – “wrestle” with the words in the book, implying an urgent and touching I-was-there-ness on its pages. But what of the strange things that sometimes tumble out of these yellowed and frequently thumbed pages , disenfranchised items that were once attached to an anonymous life?

If you are a reader and buy old books, you’ll know that the list is endless. Train tickets, theatre tickets, bills, receipts and bits of newspaper are the more frequent finds in second-hand books, but then there are also the rarer ones such as personal photos, dried leaves and flowers, maps, postcards, and even CDs. What does it feel like and what does it make one think, coming across in this way pieces from a stranger’s life, distractedly pressed between the pages of a book that may not have been revisited much any longer, and so given away?

*

Akshata Pai, a 27-year-old PhD candidate tells me the most memorable thing that she found in a second-hand book was a print-out of a photo of a young blond girl. Perhaps three or four years old, the girl is seen in a red dress and sitting in what appears to be the kitchen area, with her elbows on the counter. She found it in an old copy of Wuthering Heights, and was struck by the intimacy that the picture suggested, taken as it was in someone’s house with evidence of everyday life around it. .

She’s kept the picture because even though private, the picture gives her a glimpse into someone else’s inner life without it feeling voyeuristic. “There’s no curiosity or desire to know more. It is something that feels complete in itself,” she says. “And the fact that it was printed suggested that someone had wanted to carry it, touch it, as a tangible reminder of this child. I thought that was beautiful.”

Found photographs offer a glimpse into a stranger’s world, while disallowing the opportunity to know more, a circle of curiosity is at once opened and closed.

The very physicality of these errant items enables a sense of kinship – over both distance and time – brought about through the book, which then functions as a sort of vessel. In an old copy of Heat and Dust by Ruth Prawer Jhabwala, podcaster Laxmi Krishnan, 22, found an Indian Airlines boarding pass that was 13 years older than her, and she treasures it for that reason. “I started thinking about who might have been reading this book all those years ago,” she says.

Aadil Desai, a 55-year-old manager service engineer at Air India Engineering Services and a veritable connoisseur of second-hand book finds, has a long, interesting list of things he has stumbled upon in old books: Dried leaves and flowers in a book on Troy, pocket calendars, old exam papers from college, prayer cards, museum brochures, art gallery exhibition inaugural invites, and even hotel key card holders. He tells me that he finds it sacrilegious to put things inside books since they may cause damage and spoil the pages, but treasures the items he himself chances upon. “Just because someone forgot to remove them [the things] before disposing off their books doesn’t mean I should throw them away,” he texts me, quite matter-of-factly. “I treat all these items as an invaluable treasure to be preserved for posterity and not discarded even if the original owners did so knowingly or unwittingly.”

A collection of flowers found in second-hand books, softening pages and leaving a trace of someone else behind.

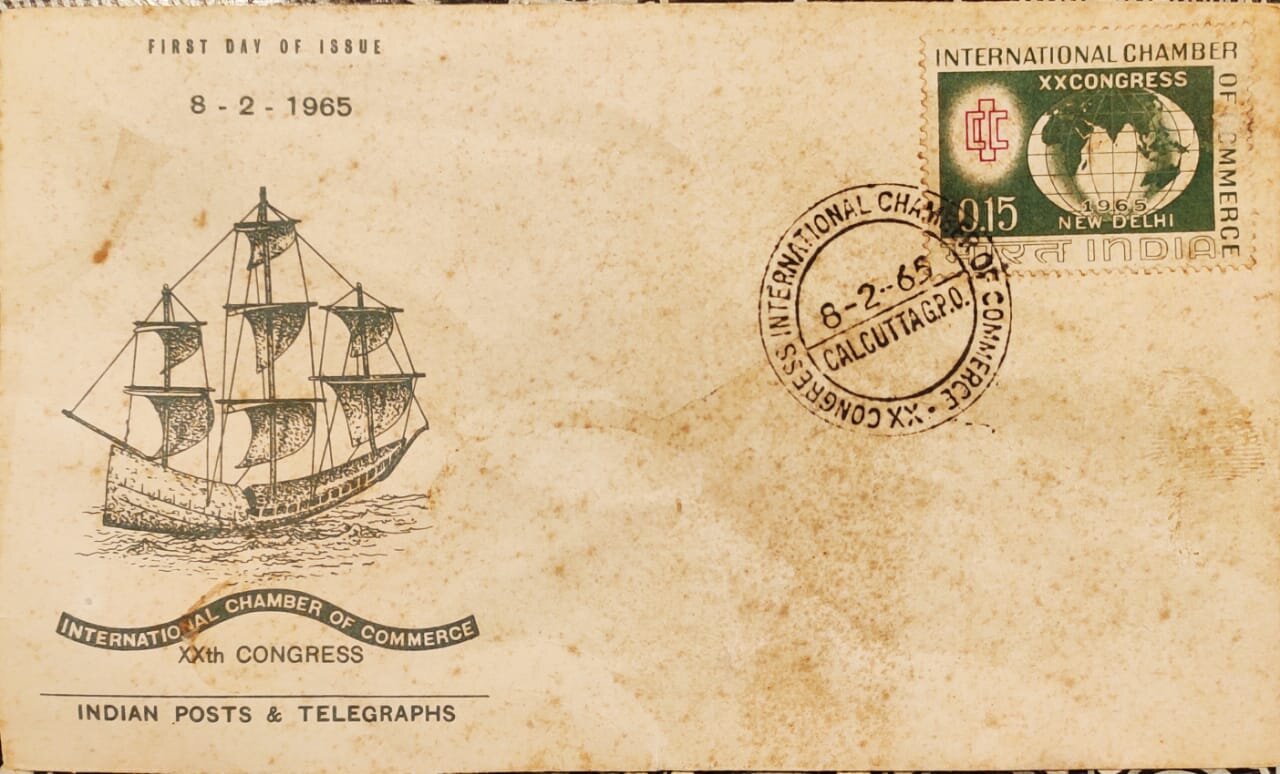

But one of his most treasured finds, he says, has been a first-day cover that was dated only a day before he was born. A personal link is so established, which makes the find all the more serendipitous, remarkable, and cherished. The book, the conduit.

A glimpse into long ago and urgent exchanges not pertinent enough to be preserved.

Looked at in a different aspect, there is also the need to go out of the way and establish a personal connection. When an object that feels intensely private lands on your lap as you turn the pages of a second-hand book, there is a strong impulse to try and reach out to its previous owner. The things you find turn into clues leading you to the mystery that is someone else’s life, rather than it being the other way round.

Twenty-five-year-old freelance photographer and writer Vedika Singhania was ruffling through books her friend bought at Blossoms in Bangalore, when they came upon Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being. Within its pages they found a Eurail pass, dated October 1989, with multiple entries for travel between Brussels and Berchem. “Along with the pass, there was a bank invoice from 1990, addressed to a certain person in London. It was very exciting to imagine the borders that this book must have crossed along with its owner/s.”

She was astounded by the fact that both the pass and invoice had landed where they had. “My friend and I later entered the address in Google Earth ,” she says, “to get a sense of whether it was all real and if the neighbourhood still existed. We then went on Facebook to locate this person by the name mentioned on the invoice. We found a match, the profile showed a middle-aged teacher. The timeline added up, so we dropped her a message along with a photo of her rail pass from three decades earlier, hoping for a revert. It must be sitting in her ‘Others’ folder in Messenger.”

Resh Susan, a writer in her thirties, is thrilled by these finds as they enable flights of the imagination. On the flyleaf of a children’s book of an illustrated psalm, she finds an address to a “daughter Hope” to whom the book was presumably given. She is particularly moved by the fact that this “daughter Hope” had so carelessly given away such a gift. Resh now thinks of keeping the book and giving it to her future daughter sometime. With a book in hand, you are in effect primed for flights of fancy, and when something curious unceremoniously falls in your hands from the book like that, it is hardly surprising that the heart yearns for some sort of narrative to explain the existence of the object.

I have found that there are a wide range of strange things to be discovered in old books. Appu S, 30, and who works as assistant manager at Reserve Bank of India once found a CD in an enormous hardback copy of Tales of the Amber Sea: Fairy Tales of the Peoples of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. The letters WCW were written on it. “My heart skipped a beat. WCW was a famous wrestling game and I had only played the demo,” he says. “I immediately put the CD into my computer. To my disdain, it was a bunch of photos of some school kids, who may have gotten hold of a digital camera and managed to take only about seven to eight photos on the same day, and had them written into a CD.” Appu threw the CD away, especially since it had given him hope and then taken it away.

Another person that has thrown away the things he finds is Sandeep Dave, a 55-year-old solicitor. He keeps “neutral” things, such as tickets, to use as bookmarks, but is firm about throwing away anything else. “I believe that each owner had a sentiment, thought or a need behind pushing something in between the pages. I cannot replicate that thought by keeping the find. If it was a personal item that the owner chose to dispense with and discard that book, I have no business keeping their thoughtless thought, and become a sentry to their past.”

But who are these people who keep things inside books anyway?

“I have often left things inside books,” Komal Seth, 49, tells me excitedly. “Bills, receipts, and anything else that was handy at a time that I needed to use a bookmark. Stickers that I like, and sometimes even rubber bands!” These quotidian items are left inside books quite unintentionally, she says. Does this mean there are things she consciously leaves inside books? Very much so, it turns out. Things such as flowers from the mandir are kept in books for safekeeping, because you can’t throw them away, says Komal. “I also keep certain photographs that I like inside books to keep them handy, so that if I want to show them to someone visiting me I know just where they are. And these are kept only in special books – books that I like.” Interestingly, while Komal keeps buying books – for herself and so also for her young son – she very rarely gives them away. For her, her books are spaces to hold personal items of her everyday life, and they serve as a place to house items too precious to throw away, like the flowers.

*

Billy Collins, the poet, talks about “anonymous men catching a ride into the future/on a vessel more lasting than themselves” in his ode to marginalia.

With the strange things we sometimes stumble upon in second-hand books, something similar, I think, is in the works. These are anonymous people leaving imprints of themselves , casually, unconsciously even, that then travel in time and space to arrive at the doorsteps of more anonymous people, touching their lives in ways they may have never imagined or intended.

Tasneem Pocketwala is an independent writer and journalist based in Mumbai. She writes on culture, identity and gender.