The Five Are Offensive Again

Megha Ramesh revisited the first Famous Five book to find out if the Five deserve their newly acquired infamy.

The details of my first Enid Blyton adventure are quite fuzzy. My guess would be a book from the Noddy series gifted to me by my grandmother. By 13, I had binged my way through most of her classics. From make-believe travels on the Wishing Chair, visiting strange lands up the Faraway Tree to midnight feasts with the posh girls at Malory Towers, her books certainly had a knack for captivating the pre-internet child’s attention.

With the Enchanted Wood replaced by Google, travels on the interwebs threw up a considerable amount of disapproval for Blyton’s work - calling her sexist, racist and classist. My first thought was ‘haters gonna hate’ because these days everything and anything is offensive to someone. But what really caught my eye was the discussion around one of the characters - Georgina/George from the Famous Five series and her gender-identity struggles. Curious to revisit her work and determine for myself what I had missed as a young Blyton fan, I settled on the first title from her Famous Five series.

5 thoughts I had while reading the Famous Five on Treasure Island

George’s Boy-Envy

“I hate being a girl. I won’t be. I don’t like doing the things that girls do. I like doing the things that boys do. I can climb better than any boy, and swim faster too.”

Keeping in mind that this book was published in the 40s, I think Blyton’s intention of creating a tomboy character wasn’t to start a conversation over gender identity, but to challenge stereotypical gender roles.

George wasn’t interested in traditionally ‘girly’ things like her cousin Anne. She was athletic, loved the outdoors and always up for an adventure. It’s quite reductive to conclude that George was gay or was a boy trapped in a girl’s body simply because she wasn’t conforming to typical gender norms. All she wanted was the freedom that the boys enjoyed. Whatever the boys could do, she could do better – and she knew it!

A strong female character that was confident, bold and brave? Blyton basically planted the seed of feminism in generations of young girls. Agreed, it wasn’t perfect, certainly not by today’s definition of feminism; but for 1942 I’d say it was pretty a good start. George was the assurance to girls everywhere that they didn’t have to make sandwiches if they didn’t want to.

I couldn’t help but wonder about 2018-George. Her short curls and pants wouldn’t be considered unusual, but at least she wouldn’t be alone in her fight for equality.

Anne, you do you.

George: Don’t you hate being a girl?

Anne: No, of course not. You see – I like pretty frocks – and I love my dolls – and you can’t do that if you’re a boy.

George: Pooh! Fancy bothering about pretty frocks. And dolls! Well, you are a baby, that’s all I can say.

The one thing I don’t agree with George on is her girl-shaming of Anne.

Between the two girls, I relate to Anne. I like pretty frocks and loved my dolls. Today we know, and accept, that one can be feminine and a feminist at the same time. Feminism is about being inclusive and supporting each other. No dress codes, rules or having someone else’s ideas forced upon you – that’s the whole point, right?

That’s where George hadn’t quite nailed it. But I’m willing to cut her some slack; it’s not easy being 11 and trying to take on the world. And let’s be honest, 75 years later we’re still divided on what it means to be feminist.

Money can buy you happiness

But Uncle Quentin was quite different now. It seemed as if a great weight had been lifted off his shoulders. They were rich – George could go to a good school – and his wife could have the things he so much wanted her to have – and he would be able to go on with the work he loved without feeling that he wasn’t earning enough to keep his family in comfort. He beamed around at everyone, looking as friendly as anyone could wish!

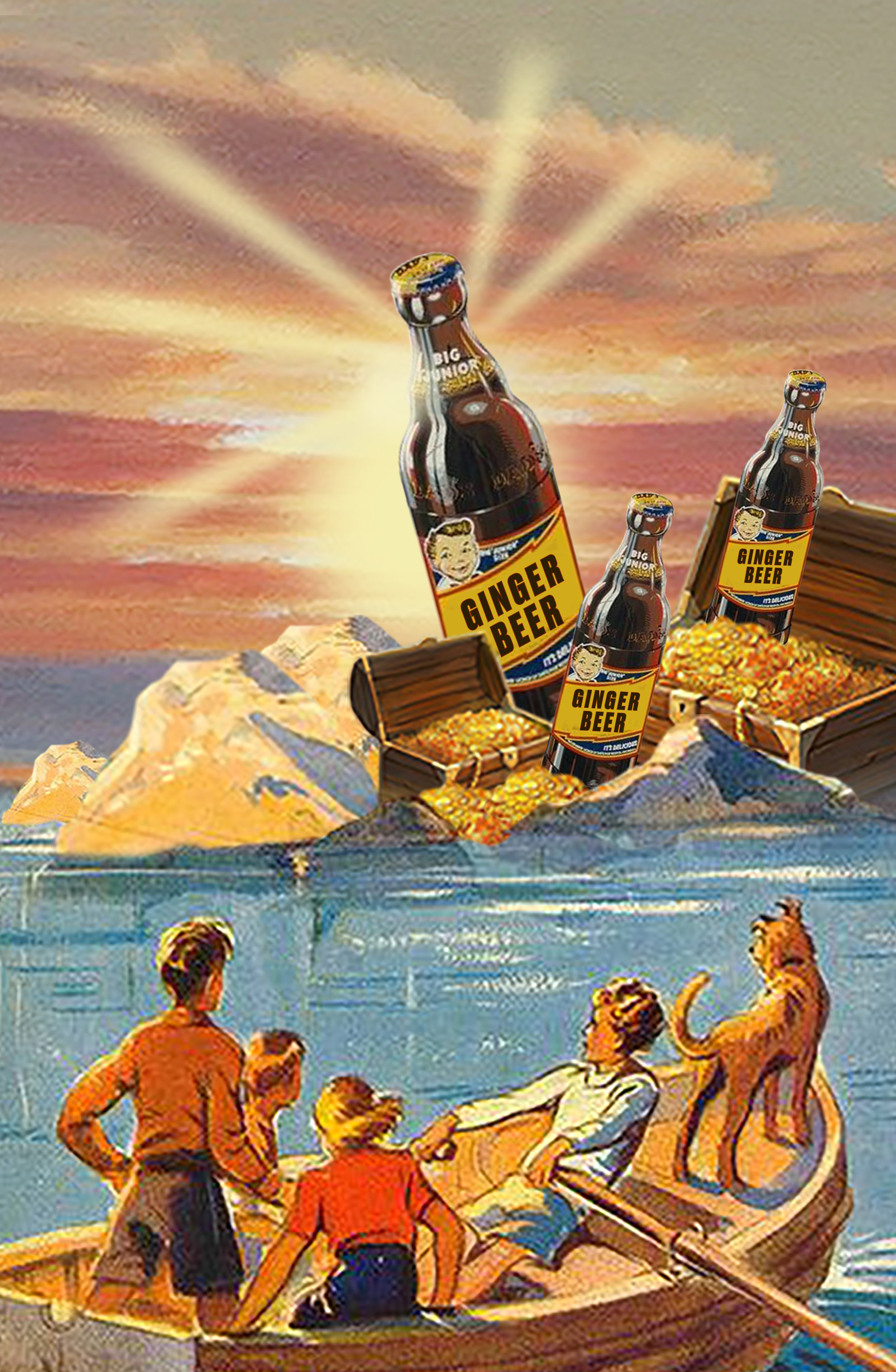

Throughout the book, Uncle Quentin is portrayed as a mean, grumpy man with non-existent patience levels – that is, until the five track down bricks of gold using a map from a shipwreck. Post pot of gold, it’s all sunshine and rainbows. Uncle Quentin was instantly a different man.

On the surface it seemed like a terrible message to send to little kids, but after giving it some thought I had to ask myself, is it really that bad?

No one can deny money does buy some level of happiness and peace of mind. At the risk of coming on too strong as a Blyton-loyalist, I think it’s actually constructive to teach kids that they should aim to earn well in order to live a comfortable, worry-free and stable life. And the upgrades Uncle Quentin was excited about seem quite family-oriented and practical.

However, the reality is that to kids, it won’t be about the gold but the treasure map and the adventure that goes with it.

#LetBoysCry

George: “I cried for days- and I never do cry, you know, because boys don't and I like to be like a boy."

"Boys do cry sometimes," began Anne, looking at Dick, who had been a bit of a cry-baby three or four years back. Dick gave her a sharp nudge, and she said no more.

George looked at Anne. "Boys don't cry," she said, obstinately. "Anyway, I've never seen one, and I always try not to cry myself.

My heart aches for the cry-shaming of Dick; and for George, who believes crying is a symptom of weakness. The ultimate sign of being a girl. Sigh.

This book was written in the 1942, and I can’t believe that today there is still opportunity to advocate that boys have the right to cry and make it seem like a radical concept.

We are all guilty of associating crying with girls; and men with being strong, and always in control of their emotions. Whenever I’ve been confronted with male-tears, it always comes out of nowhere, only to reveal the overwhelming amounts of bottled up emotion that could no longer be contained. Like George, who hasn’t ever seen one cry – we rarely witness guys let their guard down and allow the waterworks flow. With the conversation around mental health and depression increasing, we know the severity of this expectation that’s imposed on men. In this very ripe time for movements, I believe this one deserves its moment in the spotlight.

I can vouch for the therapeutic powers of a ‘good cry’ and we should all be reaping the benefits of it.

Remember when Fierce wasn’t a compliment?

I recently learnt that her books had been given a modernising makeover, you know, to be 21st-century appropriate. ‘Old-fashioned’ text was reworked, storylines adjusted and, much to my amusement, characters with ‘unfortunate’ names like Dick and Fanny were renamed Rick and Frannie. ‘Peculiar’ replaced with ‘strange’ and expressions like ‘jolly’ were deemed too challenging for kids to understand. This is where I facepalm.

Meanwhile, every time Blyton used ‘fierce’ to describe cranky uncle Quentin or George’s angry disposition, I had to recalibrate my internet-damaged brain to remind myself she wasn’t giving them the ultimate compliment one can receive today.

As much as I want to nosedive back into all my Blyton favourites, I’m worried that all I’ll see with my jaded adult-eyes are problems, overthinking every little detail. It’s impossible to enjoy children’s books with the innocence that imagination demands.

The one thing that remains unchanged from 20 years ago, is my thirst for the delicious-sounding yet completely unobtainable ginger-beer.

Written by Megha Ramesh

Art by Sharpener Design