Wild in the City

As wildlife populations grow in the city, encounters with the wild have also increased with every passing year. Urban wildlife conservation and coexistence has become a burgeoning issue. We spoke to seven rescuers and activists in urban ecologies who are helping restore our fragile bond with nature.

Beasant Nagar in Chennai is home to a shy pack of jackals, striped hyenas have been known to roam the streets of Gurugram, Mumbai has the highest density of leopards in the world and Delhi alone has more than 400 species of birds. As urban landscapes expand unchecked, a growing population of wildlife has also begun to consider these urban settlements as ‘home’. This is hardly surprising as marine and terrestrial protected areas cover only 9.67% of the planet, forcing various species to depend entirely on human dominated areas for survival. Besides this, deforestation, invasive species and climate change have further pushed wildlife to urban areas in search of better habitat. As 50% of the world’s population lives in these urban settlements, coexistence has become vital to the future of wildlife.

But how do human and non-human interactions unfold within these aggressively developing urban spaces? While cities across the world are increasingly encountering wildlife, in many ways, India is unique in how it interacts with its wild inhabitants. 1.2 million snake bites result in an average of 40,000 human fatalities, and 500 human beings die due to elephant conflicts in India every year. And yet our relationship with wildlife isn’t as bleak as one would expect. Instances of elephant-human interactions especially in agriculture centric spaces have often been referenced by sources in Indian history and literature (going as far back as Sangam poetry), indicating a sometimes fraught but largely peaceful coexistence.“Indians have an enormous tolerance for wild animals and have learnt to live alongside them. A key point that separates India from the rest,” said scientist TR Shankar Raman in a conversation with Soup. Interaction between animals and humans living on fringes of forests have long been based on a system of reciprocity, reverence and kinship. However, as more people have migrated to urban areas and lost their habitual connection to nature, this thread of coexistence has begun to fade over time.

It also hasn’t helped that in the 1990s popular media often demonised animals that transgressed into or lived in urban spaces by employing negative terms like ‘rogue elephants’ and ‘monkey menace’ in common parlance. Current conservation efforts prefer to stress on the importance of sharing spaces, quoting the utilitarian value of an urban ecosystem, where popular examples include black kites that clean up organic waste and snakes that act as natural pest controllers. Some conservationists even insist on avoiding the use of words like ‘conflict’ to describe human and non-human interactions.

But it’s difficult for these efforts by the scientific community to trickle into daily life and every day encounters. Interestingly however, this gap is filled by local rescuers, rehabilitators and passionate activists who are usually self-taught enthusiasts often working two jobs and committing themselves to conservation for a variety of reasons. These individuals often become the first point of contact in such encounters minimising risk to humans and threat to wildlife as the assurance of an immediate rescue offers safety to both sides. But what drives these rescuers to pursue their cause in the face public resistance, financial constraints, a tangled legal system and the relentlessness of nature itself?

To find out, we spoke to seven rescuers and activists in urban ecologies who are helping restore our fragile bond with nature.

CHENNAI

I.KARUNAKARAN, 61, URRURKUPPAM- facilitates olive ridley conservation

Concerned about the ‘jellification’ of the sea and the future of fish, Karunakaran has been determined to conserve sea turtles for seventeen years now.

Seventeen years ago, when Karunakaran (a fisherman by profession), read about the plight of Olive Ridley turtles in ‘Dina Thanthi’, he knew he had to do something immediately. When he learnt that fish numbers were liable to reduce if turtles weren’t protected, he felt that it was his duty as a fisherman to do his bit. Fisherman have probably been the Ridley’s original saviours in Chennai. An interview with Romulus Whitaker, who played a crucial role in starting ‘Turtle Walks’ in Chennai, indicates that until a fisherman brought in a female Ridley that he’d found on the beach, conservationists weren’t fully aware these turtles nested on the coast of Chennai. Sea turtle conservation began in Chennai in the 1970s on the east coast of then Madras, with turtle walks that documented the status of and threats to sea turtles. Today, The Students Sea Turtle Conservation Network (SSTCN) has released about 80,000 hatchlings over the past 15 years with an 80% hatching success rate.

But turtle protection doesn’t come naturally to the fishing community here, because as a child, it was quite common for people from Karunakaran’s village ‘Urrurkuppam’ (half km away from the Beasant Nagar beach by cycle) to consume turtles and their eggs. However, with an increase in awareness campaigns, the community now makes space for these turtles to nest and protects their eggs to the best of their ability.

It’s hard not to fall in love with these vulnerable creatures, which seem to inspire a protective urge in nearly everyone who interacts with them. Many student members of the SSTCN have proceeded to pursue careers in ecology, ecotourism, wildlife management and conservation, which seems to imply that to coexist, it’s crucial to understand and connect with the ecology around us. For fishermen, these connections are visceral, where Karunakaran claims that setting foot in the sea is enough to learn the way of currents, and a look at the water allows him to judge the direction of the wind. “The kadal (sea) affects the way I feel,” he says in Tamil. Some of these bonds are formed as a way of life both spiritual and existential for people who live by the sea, where before they fish, it common practice to mould damp sand into a makeshift gopuram, light camphor and offer prayers before they head to the water.

But instinct isn’t enough to save turtles, and a carefully managed routine is required especially in the case of Ridleys which are susceptible to threats from fisheries along the coast, changes in temperature, jackal and dog attacks, light pollution and their own fragile cycle of survival. To ensure their well-being Karunakaran who manages the hatcheries follows a strict schedule during turtle season where he collects eggs with students, nests them in baskets, protects the hatcheries, takes out the hatchlings and documents their progress. He does not fish during this season and dedicates himself to protecting the eggs and hatchlings, which seems essential as only one in a thousand hatchlings survive till adulthood. “I try my best and even if I can increase these numbers to two or three per thousand, I would feel I’ve done my bit,” he says.

A freshly hatched turtle makes its way to the sea for the first time in its life.

Compassion isn’t the only motivation to protect turtles, as disempowered communities are particularly vulnerable to the effects of urbanisation and climate change. Turtle conservation is therefore essential to the livelihood of those who depend on fishing for survival, and Karunakaran is all too aware of this reality. And yet, it’s impossible to not assign a relatable human emotion to the creatures he has sought to protect. “Once we rescued a turtle with about half a foot of plastic stuck in its mouth, after which we released it by boat into the deep sea. But the turtle didn’t swim away immediately, it circled our boat twice before it waded away. And I can’t help but feel that it was the turtle’s way of thanking us.”

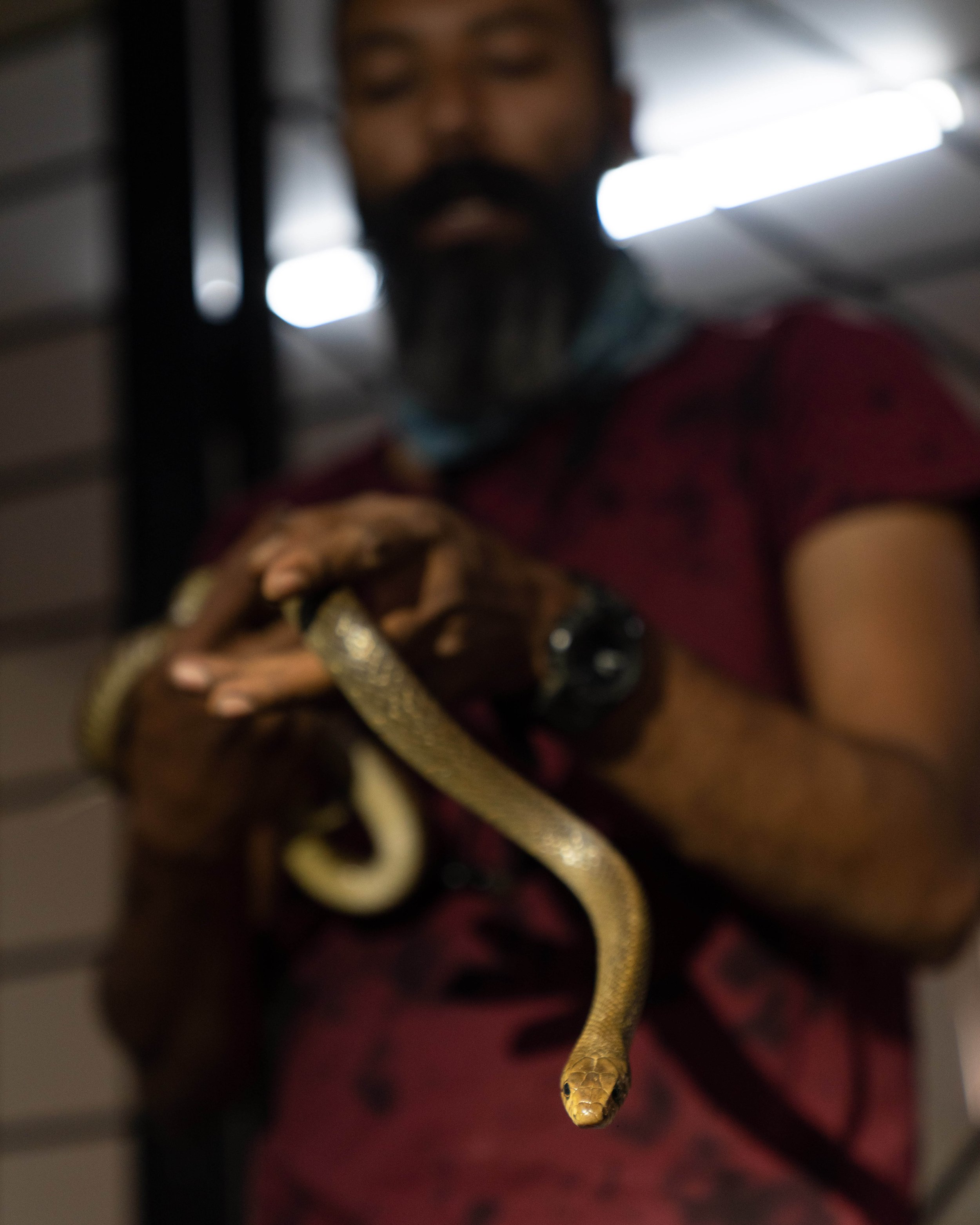

NISHANTH, 30- snake RESCUER

Nishanth also conducts an intensive Snake Walk where members of the public (most of them young and impressionable) are taught to identify a few snakes, and given factual information that helps form a better understanding of these creatures. Besides this, a non-threatening interaction with snakes, lessens the negative association snakes have in most people’s minds.

A self-taught rescuer who gleaned his knowledge from YouTube videos of Steve Irwin and working alongside eminent herpetologists like Gowri Shankar, Nishanth has rescued nearly 15,000 snakes so far. Although he is a trained Chemical Engineer, Nishanth prefers to make his living by working with Forest Departments across states and animal rescue/rehabilitation centres all over the country. For the most part however, Nishanth is based out of Chennai where he has been conducting snake rescues since 2008.

Even as a child Nishanth found atrocities against animals unbearable, and he saw plenty of these at his school which was situated in a green corridor. Nishanth recalls that school authorities killed any wild animals that entered human inhabited areas. Back then, he found himself compelled to rescue a few of these animals with self-invented methods, once even lifting a venomous saw-scaled viper with a long stick and placing it out of harm’s way. As a college student, he joined Chennai’s student turtle conservation programme, followed by other reptile-oriented programmes across the country. Although he works with a wide variety of animals including leopards, he has always felt drawn to reptiles. “People think of reptiles as disgusting looking creatures, but I have always found them harmless and shy. Even though many could be dangerous, their first instinct is to get out of our presence,” he says.

With two protected reserve forests within the city and large pockets of green areas (including campuses of educational institutions and the Theosophical Society); Chennai is home to jackals, deer, monkeys, slender lorises, snakes, various species of birds and even marine life. Since the city is in an ecological sweet spot, its residents are subject to various encounters which sometimes end badly for the animals, the most common victims being snakes. Chennai has around twenty-eight species of snakes of which only four are venomous, namely the spectacled cobra, the krait, Russel’s viper and the saw-scaled viper. When he began rescuing snakes in 2008, the public’s response was disheartening as snakes would often be killed long before rescuers arrived. However lately, he’s noticed a marked difference in the attitude of Chennai’s residents, where awareness about the behaviour of snakes, has made people more open to the idea of coexistence. Nishanth doesn’t charge money for these rescues which often happen across the length and breadth of this large metropolis. But after each rescue, he does set aside time to speak about the benefits of snakes in urban spaces, often busting myths and perceptions and encouraging residents to live alongside these misunderstood reptiles.

Rescuing in India faces a huge issue with crowd control –– a problem that puts the animal, the rescuer as well as onlookers at risk. And while rescuing cobras in particular, crowds tend to disturb the process by trying to worship the snake and further stressing the animal with camphor and agarbattis. For this reason, Nishanth usually travels with an assistant, also trained in rescue and present mainly to manage crowds. He tends to use a hook, snake bags (red to indicate a venomous snake and green for non-venomous varieties) and a common PVC pipe to conduct his rescue.

Nishanth believes that every issue that conservation faces today has been created by humans themselves. In fact, he has always found it particularly moving that most animals, don’t act out in self-defence even when violence is inflicted on them, instead they simply look to escape.

BANGALORE

JAYANTHI KALLAM, 46- rehabilitator and Executive Director, ARRC (Avian and reptile rehabilitation centre)

‘Please send picture of animal and Google Map location by WhatsApp before calling us,’ reads an instruction on the ARRC website, hinting at the organised manner in which the NGO responds to distress calls across a city which also suffers from serious traffic congestion. Jayanthi Kallam (pictured above) along with Saleem Hameed have attempted to create a state-of-the-art rehabilitation centre for urban wildlife in Bangalore.

A chance encounter with an injured American woodcock, within a sea of buildings in New York forever altered the course of Jayanthi’s life. Although she’d moved to the US as an IT professional at 23, she remembers feeling a pressing desire to do ‘something’ more than a corporate job. This encounter, and that unanswered longing led her to quit her job and train as a volunteer when she turned 35. Thereon, she worked at various animal rehabilitation and conservation programmes in the US, until she came back to India with the intention of starting an urban wildlife rehabilitation centre here.

She never had pets as a child and even remembers being afraid of animals. And her passage into the world of wild animal welfare wasn’t necessarily out of compassion but more because of the concept of ‘fairness’.

“I keep getting asked this question about what led me here but I don’t have a clear answer because it’s a confluence of so many ideas,” says Jayanthi who started ARRC along with wildlife photographer and environmentalist, Saleem Hameed. Most of Jayanthi’s ideas are rooted in theories of altruism, specifically equality. “If you think about it, animals are the least privileged and wildlife is worse off than everyone else,” she adds.

It isn’t that people in cities are unconcerned or entirely aggressive towards wildlife. “We all respond to pain, but we need an avenue to express our care.” Jayanthi emphasises. She believes that most people do attempt to connect with organisations to save injured creatures but since they often don’t have access to trained professionals, they have learnt to practice indifference. In Bangalore, a city of lakes, there are various encounters with injured birds and wildlife rehabilitation centres such as ARRC give common people an outlet for compassion. In the pandemic, as kite-flying became more frequent, manjha related bird injuries grew in number, and so did the distress calls. Last year alone, ARRC facilitated 6200 rescues. Jayanthi believes that an encounter with a wild animal only turns into a conflict when there’s no awareness on how to navigate the situation. Which is why, ARRC also organises various awareness programmes to encourage coexistence.

Most rescuers emphasise the need for standardisation where rescuers and rehabilitators are vetted and trained, so there’s less room for those who indulge in illegal animal trade. Often well-intentioned rehabilitators get dissuaded from choosing this path as it leaves them susceptible to tangles with the authorities. Urban wildlife rehabilitation is an upcoming field in India, without too many standards, precedents, clarity or trained veterinarians. Pragmatic and highly specialised in her field, Jayanthi wanted to start a centre that was ethical and organised in its approach. And since she had specialised training and because the organisation was financially stable enough to put forward strong model, ARRC has a legally validated presence in the field.

“Rehabilitation is a very demanding job. If you work with a domestic animal you get something back in terms of gratitude from the animal. But with wildlife, right from your first encounter in rescuing to the release, the wild animal looks at you as a predator. You cannot get attached to it and you still have to provide the right environment for it while knowing you will never get anything in return,” Jayanthi says.

She finds her work intellectually stimulating which is what ultimately draws her to the field. Interesting and varied species are liable to drop in at any point in the day and the task is to learn and know enough to keep them healthy and safe. In all these years of working with the wild, Jayanthi has learnt that irrespective of species, freedom is precious to everyone. “No one likes shackles, all of us are destined to be who we are. There may be dangers out there but finally, everyone just wants to be free.”

SHUAYB AHMED, 40- snake rescuer

Due to the city’s swiftly disappearing green pockets, snakes have been forced to enter urban settlements in search of food or partners. These factors have led to increased human and snake interactions, making the presence of snake rescuers like Shuayb (pictured above) essential to the well-being of Bangalore’s urban ecology.

Shuayb’s mother loved to watch cobras in the act of hooding, and as children Shuayb and his sister often accompanied their mother to see snake charmers perform. Although, he was exposed to snakes as a very young child, he wasn’t allowed to touch them. But he found himself just as drawn to snakes as his mother was. A solitary encounter with a snake charmer, who allowed him to hold a cobra in exchange for ten rupees, led to a lifelong fascination with these reptiles. “It was cold, it was smooth and I fell in love with snakes at the very first touch,” he recalls.

He conducted his first rescue at ten-years-old quite by accident, with abruptly gathered information from a television rescue he had watched. After that incident however, he dedicated his time to reading about and understanding snakes, often wandering into forest areas without permission simply to observe these reptiles. But even though he loved being around snakes, it was only seventeen years ago, while watching the unnecessary killing of a non-venomous rat snake that he felt compelled to become a rescuer.

But snake rescue is not a source of livelihood for Shuayb who runs a pet boarding facility called ‘Forest and River Shack’ in Bangalore. Despite this, he keeps himself available at all times of the day in case he gets a call. This is crucial as if rescuers do not respond to calls, people are liable to kill the snakes they encounter in what they imagine is self-defence. Mostly self-taught, Shuayb has learnt to handle snakes through seventeen years of experience through trail and error and shared knowledge from a community of rescuers to now conduct ethical and methodical rescues, with a pipe and bagger method.

While he loves what he does sometimes, rescue efforts can be dispiriting, as most people want snakes to live but they’re disinclined to allow them in their vicinity. “From what it was ten-fifteen years ago, in the past three-four years people are understanding that snakes are a part of our ecosystem. But there are still many who just want them out,” says Shuayb. He states an example of a lane in Bangalore that had seven cobras, where the community was adamant about relocating these snakes, threatening to kill them if they weren’t removed. Unwilling to take that risk, Shuayb decided to rescue the cobras, until he found a beautiful 6-foot specimen and urged the community to let it stay, as it was essential to the ecosystem. The community did not agree, eager to rid themselves of the snake. However, they were soon faced with a far more unpredictable factor in a Russel’s viper that appeared a week later. It had previously been kept in check by the cobra population. “It’s like how we live in a house, and when we vacate, someone else moves in,” he says. Amusingly enough, the community has now requested him to plant a cobra back in their neighbourhood as Russel’s vipers tend to be more aggressive than cobras when threatened.

Like Nishanth, Shuayb also holds Steve Irwin in high regard quoting him as an inspiration. In the same breath, he is quick to mention his contempt for unethical snake catchers like Vava Suresh (unfortunately dubbed by some as the Steve Irwin of India) who are more about showmanship than actual conservation. Keen to preserve the future of snakes, Shuayb has also tried to mentor a few individuals but these interactions have not been encouraging. “Often those who express interest in becoming rescuers are performing for social media and not genuinely interested in the animal,” he feels.

Despite being a continuously expanding metropolis, Bangalore still houses 33 snake species as of 2020. But there has been a shuffle in the numbers of each species, and while non-venomous populations have declined, the four venomous species have increased in number due to various factors including improper garbage disposal. Despite available data, there is no way to map species according to region in Bangalore. For instance, Shuayb narrates an incident where a large rat snake was spotted in the conference room of an office on the tenth floor. Many issues like crowd management also impend rescues in the city. Besides this, rescuers like Shuyab also have to contend with stressful situations and strenuous hours where snakes caught between difficult to manoeuvre spaces have to be carefully eased out and released.

While there may be surmounting issues in rescuing, Shuayb is keen that we should mention how Bangalore’s traffic police is particularly helpful to snake rescuers, allowing them to navigate Bangalore’s infamous traffic snarls with ease, since rescuing is a time-sensitive job. Because often enough, if rescuers arrive later than expected, people are liable to kill or injure snakes, even though this is greatly reducing now. “There is a bit more patience towards wildlife now, just a bit more, but not enough,” he notes.

GOA

ALFRED DIAGO D’MELLO, 35, nagoa (BARDEZ) - snake rescuer with Chameleon

Photographer Akshay Mahajan followed Alfred as he released a spectacled cobra half a kilometre away from its original habitat.

“It started as an accident when I was around 16-years-old,” says Alfred as he describes how his interest in snake rescue began. “There was a time when I’d run away if I saw a snake, I was so fearful. But one day, at a friend’s place, I stamped a snake unknowingly and although it didn’t attack me back, it slithered away very quickly. But in its panic to get away, it got tangled in a net. My friend’s father who was known to kill snakes in the neighbourhood, killed it immediately. But when I was disposing off the snake’s body, I felt that I saw pain it its eyes and that changed everything for me.”

Thinking back on the incident, he felt tremendous guilt that he was responsible for the death of a creature that did no harm to him. Since then, Alfred found himself wanting to understand snakes better and joined the Green Cross in college where he trained in snake rescue. Although his first experience was terrible, where he was bitten badly by a rat snake, he has slowly picked up less stressful methods of rescuing snakes. His mentor Aaron Fernandes at Chameleon, where Alfred currently volunteers as a rescuer, has further helped him finesse his technique. In his eighteen years as a rescuer he says he has saved around 4000 snakes.

Alfred is a computer technician, who rescues snakes purely out of passion, accepting only fuel charges in return for his services. And while his father doesn’t truly approve of his work, his grandmother has always been encouraging. Even going so far as to learn how handle snakes herself.

Rescues in Goa can be complicated, snakes tend to nestle on the tiled roofs of old Goan-Portuguese houses, adding further difficulties to the process of rescuing. He narrates an incident where a juvenile cobra had lodged itself onto a baby’s cradle, and alarmingly enough the baby was yanking the cobra’s tail when he got there. Alfred says he donned a helmet and a jacket, and despite the cobra striking at his helmet, managed to move the baby and later the cobra to safety.

Alfred confesses that when he began his work, the heroics involved in snake rescues did add a dimension of excitement to his work. But over the years, after working with Aaron Fernandes, Benhail Antao and other established rescuers and environmentalists, he consciously engages in ethical rescues; where personal safety is paramount, free handling is discouraged and stressing the snake is strictly avoided. The first step a rescuer learns however, is to identify snakes. There are over thirty species of snakes in Goa and differentiating between them is crucial to the rescuer, as each species reacts differently when cornered. And while king cobras have been found in Vasco city, there has by and large been an area-specific distribution of snakes in Goa.

This female checkered keelback was about to lay eggs, and therefore far less aggressive than usual during her rescue.

But the influx of new residents and other unchecked development has threatened the snake population in Goa like never before. Rampant construction has also destroyed habitats, Alfred mentions that ‘people from Delhi’ are particularly intolerant of snakes on their property. “People say they’re slimy or disgusting, but when you hold them, you just feel like they’re like smooth pipes that are alive,” he says commenting on the odd misconceptions people tend to have about these creatures. While he is in awe of the intelligence of snakes and their ‘mesmerising beauty’, he feels there is also a lot to learn from watching their behaviour, particularly how they live frugally and minimally.

NEW DELHI

NADEEM SHAHZAD, 44, old delhi- rehabilitator and founder, wildlife rescue

Nadeem refers to injured birds as his patients and maintains the same clinical reserve as a doctor when he speaks about them, saying, “we’ll have a nervous breakdown if we get emotional about each bird.” This makes perfect sense as Nadeem and his brother Mohammed Saud’s, bird rehabilitation centre has rescued 43,500 birds so far and this emotional distance simply allows them to work more efficiently.

This relationship with birds began in 1996, when the brothers came across an injured black kite that they took to the Charity Bird Hospital, a Jain-established hospital, which refused to treat the bird as black kites are carnivorous. The brothers wandered around Delhi with the bird looking to find the right care for it, but in the end they gave up, leaving the bird back where they had found it. The incident really affected them as they couldn’t understand this distinction made between birds based on their eating habits. But it was only in 2003 that they first began rehabilitating birds themselves, after they took an injured black kite back home and got it treated by a local veterinarian, Sunil Shrivastav. After that, they continued this practice, soon converting their roof into an enclosure for injured birds. By 2010, the brothers had registered their NGO ‘Wildlife Rescue,’ and ever since they’ve focused on rehabilitating birds of prey and water birds. They’re now the world’s biggest raptor rescue facility, based purely on their intake of injured birds.

The brothers are internationally recognised now as a documentary based on their work, ‘All that breathes’ (not released in India, yet) has been doing the rounds of various international film festivals. The documentary made by Shaunak Sen even won the Grand Jury prize at the Sundance film festival this year. Despite the buzz around them, Nadeem says that their NGO is still in dire need of funding. The organisation’s expenses — equipment, veterinarian, transportation and more than 500 pounds of meat every month — are hard to manage on the donations they receive. It’s therefore primarily run at their own cost, which means even though they work 12 hours a day at bird rehabilitation they must continue to run their liquid soap dispenser business by balancing hours between them.

Nadeem says he has always had a connection with black kites, where even as a child both brothers interacted with the birds quite often in their neighbourhood. The Muslim community in Old Delhi believes that feeding these birds can help earn religious credit. And so, a tradition of feeding these raptors with scraps of leftover meat has led to a thriving black kite population in Delhi. Besides this, black kites are scavengers and manage to find opportunities to subsist on the city’s burgeoning mounds of garbage. More than 400 species of birds exist in Delhi as of 2020, where besides native populations, various water birds and terrestrial birds cross international borders to visit Delhi during winters as it falls on their migratory path. Often enough, the brothers find unique ‘patients’ visiting them, notable amongst these being a Peregrine falcon and an Eurasian hobby.

The most common injuries that affect birds in Delhi are manjha thread related, despite it being a legally banned product. These minute and intricate injuries and unknown species of birds that come in regularly, have ensured that the brothers have trained themselves in rehabilitation to offer the best possible service to those under their care. The first step in training, like most rescuers say, is to identify the bird and then plan its nutrition, care and treatment. Some birds must be left in open areas while others like barn owls need dark, closeted spaces for rehabilitation. And hunter birds like ‘shikra’ also commonly found in Delhi require a very particular kind of feeding and care.

Nadeem may try to detach himself emotionally from the birds, but he has experienced instinctive trust from these animals where they display a willingness to be held, treated and cared for. Ultimately over these years of rehabilitating birds, Nadeem has found that birds are just like us. “We are traumatised in similar ways and worry about death in the same way.”

MUMBAI

GEORGE REMEDIOS, 37, MUMBAI- environmental activist and founder, Turning tide

Within a tightly spaced food forest adjacent to Bandra’s bustling Hill Road, mounds of mulched leaves part to reveal a forest of moths, shy families of slugs, ribbons of earthworms and bouquets of fungi sheltering within the arms of old and new trees. These forests are also home to sun birds, squirrels and other small animals that exist within the ecosystem of trees. “Trees don’t provide oxygen, as is the common conception goes, instead they create micro-climates within which other life can thrive,” says George Remedios who has planted ten such forests across Mumbai.

George founded Turning Tide seven years ago with a desire to cultivate lush food forests within small pockets in urban landscapes. He felt the need to act urgently when the residential area he grew up in began to change drastically. The birds and small animals were the first to disappear. But George was further alarmed when he traced a pattern of respiratory illnesses amongst the people in his neighbourhood due to rampant construction that had begun around his home.

His first project was an almost amateurish effort, where he and a few friends sold a bunch of newspapers in their neighbourhood to collect money to buy saplings. But while these saplings didn’t all grow into trees due to a number of reasons, including the quality of the soil- it was still a beginning. After a few trails and errors, George then began by planting around his own neighbourhood, starting with bamboo bushes which offered thicket-like cover to his building. Today Turning Tide has planted around ten food forests in Mumbai where mangoes, coconut, papayas, guavas, pomegranates, bananas and Indian jujubes flourish in small but purposeful patches of rebellious green within a sea of grey.

These pockets of greenery have invited back not just the birds, squirrels and monkeys but also a quieter network of insect life, invisible but crucial to the health of urban ecologies. And since Mumbai has lost nearly 40% of its green cover in just 30 years, these green spaces spell hope for city.

Within six years, ‘Turning Tide’ has planted 1,000 trees, 80% of which survive despite various stresses and triggers around them. George finds it easiest to plant within institutions like orphanages and old age homes as they have better managed after-care systems, because follow ups are crucial for the health of trees. “Every sapling lost, hurts,” says George recalling an incident where twenty pomegranate trees were destroyed by mismanagement. Not only are trees fragile, an average tree can take anywhere between ten-thirty years to grow, making George’s work, the kind of labour that will transcend his own lifetime.While making sense of the many intricate factors that define the growth of a sapling, a Chinese saying comes to mind, one that answers its own conundrum; 'When is the best time to plant a tree? Twenty years ago.’

George is therefore mindful of the species he plants, careful that they shouldn’t interfere with the existing environment or turn into harmful monoculture forests. His food forests are not just an invitation for animal life, but also a way to reinstate the city’s connection with nature. George who is ethnically Goan, has always felt an affinity for nature, be it with the birds that visited his home in Santa Cruz or the trees he planted with his grandmother in Goa. And there is admittedly, a sanctum-like atmosphere in George’s urban forests where residents find not just cooler environs, but also a modicum of peace from the bustle of the city.

Starting the NGO has been far from a smooth ride. Ever since he quit an advertising job to dedicate his life to trees, he has had two debilitating accidents, but he says that these travails have only reaffirmed his need to serve a greater purpose. “I’ve been called the village idiot and other names. Even at my own home, there was resistance. But today people are seeing sense in my work,” he says. He feels that every sapling that grows into a tree, is an accomplishment. “I’ve learnt a lot about myself by working with trees. The positives and negatives aside, what I’ve really learnt is that a change can be made.”

Photographed by:

Chennai: Kirthana Devdas

Bangalore: Gayatri Ganju

Goa: Akshay Mahajan

Delhi: Menty Jamir

Mumbai: Hashim Badani

Story and interviews: Meera Ganapathi

Special thanks to Amrita Neelakantan, Urvi Gupta, Nishant Kumar, Yatin Kalki and Tarsh Thekaekara