The closeness of isolation

Isolation should imply solitude or loneliness but for a country like India, could it also mean an overwhelming togetherness? Ankita Shah speaks to families, strangers and friends quarantined together to find out how they’re coping with this enforced closeness in unique ways.

The word isolation has now become a paradox. It denotes ‘separation’ or social ‘distancing’ as we’ve come to understand. And yet for some, it mirrors proximity. While we’re all following distancing rules with those outside our homes, what does distancing mean when it comes to those we’re cooped up with? As we desperately wait for the lockdown to end, some relationships at home are being renewed. So many of us are ‘isolated with’ parents, siblings, children, partners, or in some rare cases, strangers. We have never spent so much time with them before, and definitely not under these circumstances. It is here, that isolation also becomes contact. And the malleability of the word rubs off on our relationships, revealing a new world.

For Agatha Pradhan, a 21-year-old student in Siliguri, and her sister, a month in quarantine with their parents has uncovered new sides to them she didn’t know existed.

“My mother is a nurse and has been in service for the past 30 years. My father is unemployed as of now, but worked as a medical transcriptionist when we were growing up. My sister and I have been on our own for as long as I remember. Suddenly, I am aware of the years I spent with my parents yet never got to know them. I am seeing them for the first time as individuals with their own hobbies and unique outlook on life.”

The four of them share cooking and cleaning duties. But it’s the meals shared together that Agatha says she’ll cherish the most when all this is over. There’s also a fifth member in the family cooped up with them – her cat. “Phoenix is paralyzed from the waist down and requires a lot of help on a daily basis. Lately, my Papa offers to feed Phoenix and take care of him. I have always taken Papa to be indifferent to those around him. He rarely talks to neighbours and only a few of my friends have interacted with him. It’s cute to watch Papa and Phoenix snuggle in bed.”

But being too close can often invite friction. “We're a family of four living in a twenty-year-old 2BHK flat, there's only so much space- physical and emotional, that one is allowed. It is uncomfortable to be in such close proximity to each other's personalities. We get into heated arguments. Even when one is upset, there's no room to shut oneself in. I often go up to the terrace to have a good cry after such fights.”

But Agatha says they’re slowly beginning to respect boundaries and each other’s individual opinions. “Our days were lived in such a rush that if it wasn't for this period of lockdown we'd be just four strangers living under one roof. Through the years, we'd drifted apart due to a rough patch in my parent's marriage. The lockdown has brought the four of us face to face to see each other in all our flaws, to accept the short-comings; and to forgive one another.”

While for some, isolation is redefining connections with those they have lived with for years, we spoke to someone who has built a unique companionship with a stranger.

Sohini is sharing an unknown space with a complete stranger and finding an uncertain sense of ‘home’.

Sohini A, 32, event producer, was in Calcutta for an event when the lockdown was announced. As someone who is immunocompromised, she did not take the risk of travelling back to her work base in Bombay. Her cousin had a vacant flat and immediately helped, so she could comfortably wait it out. One day, Sohini’s sister-in-law received a call from an acquaintance who was hiding in her room after her husband had beaten her. She had been going through this for 8 years but since the lockdown started - the abuse had increased. “She called the police and then requested my sister-in-law to provide her an asylum for a few days in her home (this vacant house) till she figured the remaining bit of it.” The police along with her cousin dropped her to the place Sohini was living at.

So, this otherwise empty flat now housed two women, strangers to each other and to this ‘home’. Does it get easier to balance solitude and company with those you don’t know? Sohini says, “Many, many years of being in boarding school and having roommates has taught me to clearly demarcate my boundaries. We stay in separate rooms and have a separate schedule and are cordially polite towards each other’s need for space.”

Besides, this is not the first time Sohini has known isolation. Being a grade IV endometriosis patient, having undergone surgeries and multiple hormone treatments to keep her going on a daily basis - cut her out from the world for almost a year. “When you are diagnosed with something that is life-altering - people come by with condolences and try to be around, in the beginning. But eventually, people move on - weddings, holidays, parties, new cities, the next relationship. I would then just move from home to hospital and back home. Work from home on days I could or else sleep through it all. Now, I'm better equipped to handle the anxiety of this stillness.”

Surekha misses work but values the time she’s found with family.

Surekha Jadhav, 30, our help, says the lockdown has brought her close to her children but the indefinite nature of the quarantine bothers her. She tells me, “I lost my husband six years ago. And ever since, I’ve been working. I have three children, my eldest daughter is 13, the younger one 10, and the youngest son 8. The four of us have never spent this much time together before. They’ve become more mischievous now – there’s never a dull moment with them around. But at the back of my head, I’m worried about work. I want life to get back to normal. I want to go out and work again.”

Strictly contained with limited movement can get suffocating. “A typical day involves cooking, cleaning, watching some television, and making sure the kids are studying (the school sends study material and homework through WhatsApp). But I get bored every now and then.”

I ask her what she and her peers feel about the future prospects of their work. She says, “We’re hoping that in a month or two things get back to normal. We are all getting paid on time. In fact, our employers call us up and coordinate, we don’t have to follow up. But I want my work to resume soon so I can demand my salary and really feel I have worked for it. It doesn’t feel nice to take this money otherwise.”

For Surekha, while isolation brings her closer to her kids, it separates her from the daily work-life that she identifies with as the sole bread-winner. She only hopes things get back to normal soon.

The word isolation isn’t that old. While it originated from the Latin word insula, the first recorded usage was in the late 1700s in its French form isole. But the vocabulary of distance, of separation, only keeps expanding. Closer home, the people of Jammu & Kashmir (J&K) were legally cut off from the rest of the country as a consequence of “integration”. Since August 5th 2019, the state is under a security lockdown. Despite protests to lift this lockdown, not much was changed. But a month ago, a version of this lockdown was imposed on the world too. And yet, it’s not the same. Belinda Peter, Tarun Bhalla, Karishma Prakash, and Juhi Siddique work at a school in a remote mountain village of Breswana in J&K. They’ve been working and living there since August last year. Belinda writes in her email, on behalf of the four of them isolated together, “Isolation before meant something voluntary, something you did by choice. It also meant something that had an expiry date. It still feels less cruel than the post-August 5 crackdown - because the world seems to be facing similar circumstances.”

Despite working together and living together under grave circumstances in the area, working with children, with a sense of solidarity, it has taken this pandemic-led lockdown for the four of them to finally become more friends than colleagues.

“We spend the mornings assigning homework via WhatsApp to students. Two of us have started learning Urdu together. We do yoga together. We spend the evening trying to cook up interesting meals with the supplies we have. Electricity and gas have to be used judiciously given that it’s hard for resources to reach us.” says Belinda.

“We are pretty good about sharing the load. If one person is cooking we all hang out so someone else does the dishes. The same goes for cleaning. Again, it helps to be isolating with responsible adults. Two boundaries we’ve laid out- 1. Morning is for alone time. 2. K’s “yes!” means stop talking I have heard you.”

Meenal Upreti, 22, is a photographer and assistant director from Uttarakhand, currently living in Delhi. She shares a 3BHK with her old college friends. While one of them managed to go back home before the lockdown, she and her roommate Suraj couldn’t get back in time. While her family has been told she shares the apartment with a girl, they are not aware of her male roommate as this information is unlikely to sit well with them. So they believe she is currently living alone in Delhi and this has led to long reassuring calls back home to convince them she’s doing alright.

While Suraj and Meenal were close friends back in college, the routine of day jobs and different work hours had turned them into mere roommates. They would bump into each other for late-night dinners before they all retired to their own rooms. But ever since the lockdown, with only each other for good times and bad, they have become family.

“I recently had throbbing chest pain. I couldn’t tell my parents, but I didn’t feel that I don’t have family here. Of course, I went to the doctor on my own, because we didn’t want any more exposure to the virus, but Suraj was always here taking care of me.”

Meenal’s relationship with her friend is changing, but so is her relationship with her sunlight-deprived house. As both a photographer and a nature-lover, Meenal chases light – but has found herself locked down in a house with no ventilation and a bedroom room with no windows. “After eating, we plan on some portrait and product shoots with natural light – like, we were eating watermelon and we decided to do some fun stuff with it. The only time we get a bit of sunlight in our house is between 3-5 pm. We try to make use of it, as much as possible. There is no pressure; we are just trying to enjoy ourselves as we did in college. We are actually reliving our college shoot days through this.”

And so Meenal’s days are filled with a desire for stories that are a play on light’s meagre presence in her life. “My work life was also an issue in the past when I couldn’t open up to anybody about it. I had not been shooting for almost a year, because I am a fresher in the industry. This lockdown is really helping me vent out that anguish on what I love the most – telling stories through visuals. I now look for inspiration in everyday things like a glass of water, a lemon wedge, my own body and little moments out of my window. I am glad that I can chase the light like never before.”

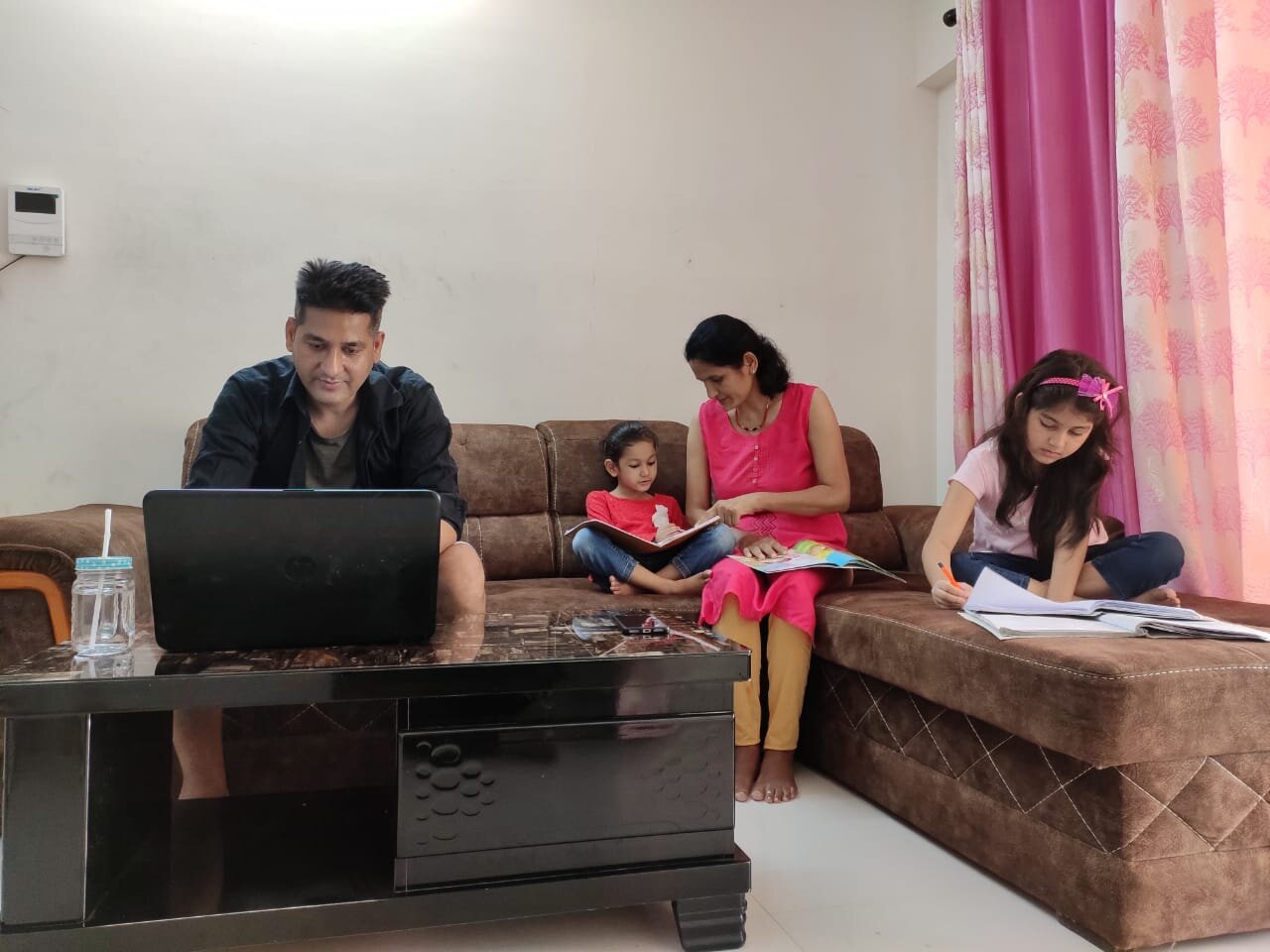

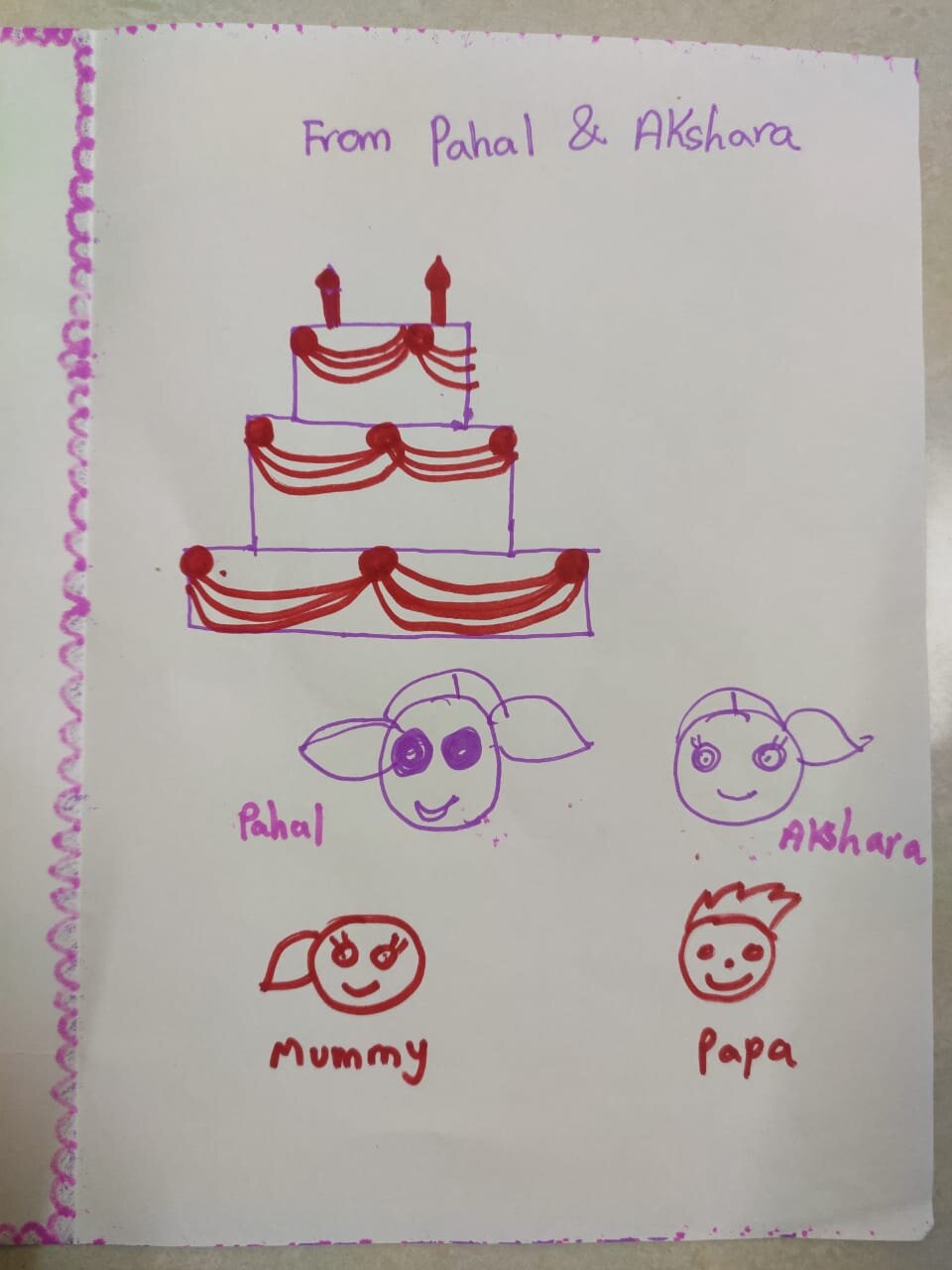

Lakshman Sirola, 35, is a cinematographer. With innumerable shoots at odd hours, his recent move from a rented home in Andheri to his own 1BHK in Virar did not prove conducive to his work-life balance. “Because most of the shoots are around Andheri, I often have to stay over at a relative’s place to reduce travel time. After moving to this house, the quarantine has finally given me an opportunity to spend time with my wife and my daughters.”

“While I’m worried about my job and the future of this industry, I’m also working on some projects and spending time in research to expand my skills. I’m learning editing now as well. Meanwhile, my days are very different now. My wife has been suffering from arthritis the last few weeks, and I’ve naturally taken to chores that she used to do. I feel it’s my duty, after all these years of her supporting me, it’s my turn to take care of her and my children. I wake up early every morning and make breakfast, then lunch, and then have regular video meetings from 11-12. In the evening, Tanuja, my wife, and I sit in the balcony for an hour or so, just talking and having tea. After dinner, it’s movie time. We pick a film and by midnight, we all retire to bed.”

What about time alone? “My daughters are young but mature enough to understand if I ask them to not disturb me for some time. I take the living room and tell them to be in the bedroom with my wife when I’m working. But I catch up with them when we do gardening together or when I see their dance practice”

Amidst the uncertainty of it all, Lakshman says he’s grateful for the time he’s spending with his family.

It is in these many manifestations that isolation becomes closeness, becomes solidarity, becomes a catalyst for the old to be renewed, and a seed for something entirely unexpected. This precious, difficult, limited and yet seemingly indefinite time is rare, it is unlikely to come back again. As we let it into our homes, we will find that we’re creating a wormhole of shared experiences and realities that we will forever cherish.

And while the effects of closeness are many (including a lurking invisible threat), the journey of staying together through a crisis like this is a test of both vulnerability and patience – and we’re all in this together, literally.

Photos provided by subjects.